Spirit Not Commodity

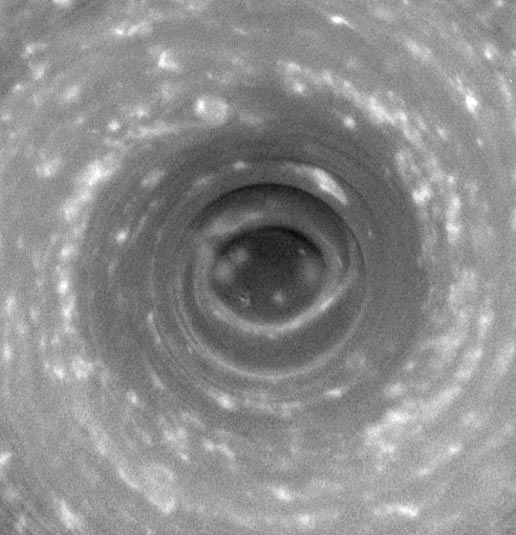

The strength of Thomas Merton's prophetic voice was particularly potent is his ruthless observations of what mass media, mass industry, and mass technology were doing to the human spirit, leading us to a potential abyss of Orwellian visions come alight to destroy our privacy, our integrity, and our worth as individuals. Speaking from the platform of the 1960's, his observations, concerns, and calling out reach to us even sharper today, as we look towards a “Blade Runner” future that looms like a whirlpool before us, inexorably sucking us in.

He writes:

“The Greeks believes that when a man had too much power for his own good the gods ruined him by helping him increase his power at the expense of wisdom, prudence, temperance, and humanity until it led automatically to his own destruction.

What I am saying is, then, that it does us no good to make fantastic progress if we do not know how to live with it, if we cannot make good use of it, and if, in fact our technology becomes nothing more than an expensive and complicated way of cultural disintegration...The fact remains that we have created for ourselves a culture which is not yet livable for mankind as a whole.”

This immersion in the glittering silicon progress becomes a drowning of our spirit when the flickering of the TV and computer screen replaces the connection to our conscience, and when the voices from these screens become unquestioning authorities in our life beyond philosophical and moral reproach.

One question essentially sticks out: Is our technological age, an age of human progress beyond apparent limit, even the “limitation” of sacrifice and obligation to God, actually creating a better present and a better future? Are we actually progressing, or is this a terrible illusion?

Merton is not hopeful of this progress if the forces of material science and technology are allowed to rule without careful consideration of their consequences, or without any link to the spiritual realities and obligations of selfless love and care. He writes:

“The central problem of the modern world is the complete emancipation and autonomy of the technological mind at a time when unlimited possibilities lie open to it and all the resources seem to be at hand. Indeed, the mere fact of questioning this emancipation, this autonomy, is the number-one blasphemy, the unforgivable sin in the eyes of modern man, whose faith begins with this: science can do everything, science must be permitted to do everything it likes, science is infallible and impeccable, all that is done by science is right.

The consequence of this is that technology and science are now responsible to no power and submit to no control other than their own...Technology has its own ethic of expediency and efficiency. What can be done efficiently must be done in the most efficient way-even if what is done happens, for example, to be genocide or the devastation of a country by total war.”

This struggle between forces of power blind to ethics going against the spiritual way of life, of a developed humanity steeped in compassion and the depth of awareness, goes to the very heart of our individual and collective existences. If our society is geared to the mass forces of blind power and profit, buttressed by the increasing paradoxical sense of control/anarchy that comes from the misuse of science and technology, then we are only geared to our lower nature, to our lust, greed, and envy. We will remain senseless in all senses to our spiritual heritage, what to speak of the realm of ethics which comes from that heritage.

We are fully dynamic spiritual individuals, capable of the highest and deepest love with each other and with God. If we choose to give ourselves without compulsion and contemplation to this inhuman and impersonal machine of power and profit, we become like that machine, like unfeeling and incomprehensible animals running only on a perverted instinct.

We have chosen to become numbers, commodities, products, anything else but who we actually are, anything else but our natural, spiritual being. From this, we suffer in unspeakable ways, bringing this pain deep into our own existence and into the existence of all other sentient life.

Merton writes:

“It is by means of technology that man the person, the subject of qualified and perfectible freedom, become quantified, that is, becomes part of a mass-mass man-whose only function is to enter anonymously into the processes of production and consumption.

He becomes one side an implement, a 'hand', or better, a 'bio-physical link' between machines: on the other side he is a mouth, a digestive system and an anus, something through which pass the products of his technological world, leaving a transient and meaningless sense of enjoyment.

The effect of a totally emancipated technology is the regression of man to a climate of moral infancy, in total dependence not on 'mother nature'...but on the pseudonature of technology, which has replaced nature by a closed system of mechanisms with no purpose but that of keeping themselves going.”

The basic problem is that our character is stained on a very fundamental level at the base of our being. This stain is, as mentioned above, our deep inner hypocrisy and selfishness. The rise of technology is, in many ways, reflecting this stain out into our external world. Somehow, by our unyielding and often merciless intelligence, we have discovered how these mystic powers can be best used to shape our way of life, but because we have largely lost our sense of responsibility towards our self and towards each other, we use these powers to create a situation largely intolerable towards the cultivation of our deeper spiritual reality.

From his vantage point in the early 1960's, before our time of instant thought transmission and criticism via 24/7 news cycles and all-pervading social networking and observation, Merton's prophetic voice rings out to us to understand our stain, to understand our sickness, and to do something about it. He writes:

“The greatest need of our time is to clean out the enormous mass of mental and emotional rubbish that clutters our minds and makes of all political and social life a mass illness. Without this housecleaning we cannot begin to see. Unless we see we cannot think.”

He continues:

“Nothing can take the place of thoughts. If we do not think, we cannot act freely. If we do not act freely, we are at the mercy of forces which we never understand, forces which are arbitrary, destructive, blind, fatal to us and to our world.

If we do not use our minds to think with, we are heading for extinction, like the dinosaur: for the massive physical strength of the dinosaur became useless, purposeless. It led to his destruction. Our intellectual power can likewise become useless, purposeless. When it does, it will serve only to destroy us. It will devise instruments for our destruction, and will inexorably proceed to use them...It has already devised them.”

The committed spiritual activist thus deeply understands the imperative need to purge and purify the consciousness and the space in which our consciousness interacts. Through this cleansing, the truth, the actual spiritual truth, can shine through, can be visible again. When this torchlight of actual knowledge shines through, the darkness born of ignorance has no place to stand.

We may take to the streets to protest and to even give our lives against the corporate, industrial, and military structures representing and implementing the interests of this cold, impersonal machine. We may consider ourselves as no longer a “blind follower” of this machine, of possessing an individual integrity that refuses to be crushed under tank wheels and wireless radiation.

Despite this conviction, we need to look at the actual, bigger picture. Do we actually succeed in what we set out to do, in the revolutions we attempt to create? Do we actually overthrow what we set out to overthrow? Do we even understand what success is? Do we know what it takes to set one apart from the impersonal flow towards an actualization of being? What the committed spiritual activist can offer in this arena is an understanding of our self and our predicament that transcends the cold, impersonal machine within us, a machine that runs on the oil of selfish greed. Within us instead is a greater and more bold power, the power of God nourished and nurtured by our faith put into action, into expression, and into an undeniable reality.