Inspired by my readings of "Contemplative Prayer" and "Contemplation In A World Of Action" by Thomas Merton

Inspired by my readings of "Contemplative Prayer" and "Contemplation In A World Of Action" by Thomas MertonWe often talk here in the Bhaktivedanta Ashram of going outside our "comfort zone" in order to prove ourselves worthy of the inspiration and blessings that we need to become sincere sadhakas and spiritual warriors.

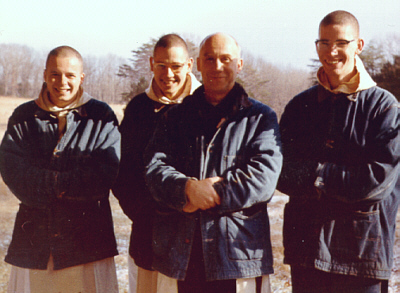

In a recent class, our wise and fearless guide HG Yajna Purusa Prabhu gave an essential purport to this personal challenge: Our souls are designed to relate, to go deep into relationships, becoming vulnerable, honest, pure, sincere, and determined.

Because we have never been trained how to do this (I can only speak deeply of my own feelings of uncertainty in this department), to make this effort and to clear the muddled path to allow ourselves to reach our natural state of relation and syncopation on the level of Divine Love is a existential task that confounds even the best of us.

In our sadhana, we are given the essential key to opening up the path inward to achieve this state of grace: a constant prayer and meditation that connects us to Krsna in the most direct and palatable way. In Contemplative Prayer, Merton writes:

"Prayer...means yearning for the simple presence of God, for a personal understanding of his word, for knowledge of his will and for capacity to hear and obey him. It is thus something much more than uttering petitions for good things external to our deepest concerns."

To become at all serious in our spiritual drive, we must strive to deepen our conceptions of what real prayer is. We cannot treat our prayers as abstract expressions of our material will. We cannot treat our prayers as daily rituals to be finished on or off schedule.

Observe any devotee, any serious spiritualist, whose prayer is the focus, the calm eye of the storm in the midst of the raging hurricane that is the Kali-Yuga, and you will see someone connected, wireless and flowing to the eternal.

Our prayer, our meditation on the Holy Names, if we can do like this and make it the central foundation holding up all our externals, and allowing it to lift us off the bodily and mental platforms, will allow us to break through to our true identity, beyond our "comfort zone". Merton writes:

"My true identity lied hidden in God's call to my freedom and my response to him. This means I must use our freedom in order to love, with full responsibility and authenticity, not merely receiving a form imposed on me by external forces, or forming my own life according to an approved social pattern, but directing my love to the personal reality of my brother, and embracing God's will in its naked, often impenetrable mystery."

This gift of the depth and breath of our prayer, letting our tongue reach out and even try to taste the Holy Names, feeling it mixed in with the scents of kadamba flowers and fresh cow dung, is a grace that has taken us millions of lifetimes to take hold of.

If we wrap our prayer in the attitude of gratitude, with the soft spice of humility, we will never lose hold of this most precious meal for our soul. Merton writes:

"We must approach our meditation realizing that grace, mercy, and faith are not permanent inalienable possessions which we gain by our efforts and retain as though by right, provided that we behave ourselves. They are constantly renewed gifts...it is never something which we can claim as though by right and use in a completely autonomous and self-determining manner according to our own good pleasure, without regard for God's will...the gift of prayer is inseparable from another grace: that of humility, which makes us realize that the very depths of our being and life are meaningful and real only in so far as they are oriented towards God as their source and their end."

Merton, in developing the realizations of the essential importance of humility, implores the serious seeker to place himself vulnerable and pleading before God, in order to become absorbed in the most sincere and potent meditation. He writes:

"Our meditation should begin with the realization of our nothingness and helplessness in the presence of God. This need not be a mournful or discouraging experience. On the contrary, it can be deeply tranquil and joyful since it brings us in direct contact with the source and joy of all life. But one reason why our meditation never gets started is perhaps that we never make this real, serious return to the center of our own nothingness before God. Hence we never enter into the deepest reality of our relationship with Him."

It is actually as asset of our greatest strength that we can place ourselves before Krsna like this, which gives us, by His mercy, all the creativity and vitality we need to stay committed and caring.

Of course, raised up in our culture of emotional instability, we must try to transcend using this feeling of helplessness to remain hopelessly on the mental platform, over analyzing every little fault of our imperfect character, and overly depending on others to define our experience for us.

Merton demands us to dig into our own hearts, beyond the comforts of our mental speculations and machinations. To do this, we must soak up courage from our prayer and meditation with unfettered determination and desperation. He writes:

"Finding our heart and recovering this awareness of our inmost identity implies the recognition that our external, everyday self is to a great extent a mask and a fabrication. It is not our true self. And indeed our true self is not easy to find."

But find it we must, and we must arrange our lives in such a way, in whatever sacrifices of the nonessential that we must make, to put our prayer, the Holy Names, at the first and foremost center of our consciousness.